One afternoon nearly 50 years ago, a 16-year-old farm girl named Rita overheard her father talking with another man. They were discussing the beleaguered state of the American small farm. The man was Mr. Arnold, a farmer near Le Roy, and the father of Rita’s new boyfriend George.

Rita couldn’t help but overhear. That world is dying, they said. It’s too hard a life, they said.

Rita knew that the men were talking about her future, too. She piped up. “Wait now — well, what about George?”

“He’s dying, too,” declared her father. “All of us small farmers.”

Rita thought but didn’t say: What are we going to do?

STILL, she loved George. They’d met a few months earlier at a church convention and knew very soon after that they’d be married. After high school, Rita studied to become a nurse and George, like the men in his family before him, turned his hand to farming, biding his time until Rita had finished up her schooling.

THE PAIR married in 1975 and moved onto a small plot of land “down by Turkey Creek,” as George describes it, “just south of Abbott Crandall’s place.” George farmed. Rita took a job as a nurse at Coffey County Hospital.

IN 1976, the young couple was returning from a short road trip into Missouri. Somewhere around Fort Scott, off Highway 54, Rita spotted a homemade greenhouse rising up from someone’s backyard. “I’d like to have one of those,’” George remembers his new wife saying. “I guess she thought it would be fun.”

THE NEXT winter George and his father built a 10’ x 16’ pole-frame greenhouse, and by the spring of 1977 the young couple had a small crop of tomatoes, peppers, and marigolds on their hands.

IT WAS AS true then as it is now that a person can eat only so many tomatoes, and so, while Rita would carry seedlings down to the hospital to sell to her colleagues out of the trunk of her car, George began selling his vegetables and flowers to area Duckwall’s stores and to some of his neighbors and friends.

IN 1983, a few years after the death of George’s father (“You couldn’t ask for kinder, gentler person than what he was,” remembers George), George and Rita took up residence at the farm where George was raised, a wind-swept patch of prairie that has been in the Arnold family for more than 100 years.

“WE SETTLED here in the summer of ’83,” recalled Rita. “We covered the very first roof of our commercial greenhouse on December 13, 1983. Our first season to be open as a commercial greenhouse was the spring of ’84. We tore down chicken houses and put up more greenhouses as needed. Anyway, it’s just gone on from there.”

ii.

“HELLO, this is Arnold’s Greenhouse. May I help you?” George Arnold presses the phone to his ear. “Now, what’s that again?” He covers his left ear with his free hand. “Tame ones?” he says. “OK, let me check for you.” George leaves the garden center’s makeshift conference room and wanders out into the 80,000 square feet of sunlit nursery that today makes up Arnold’s Greenhouse, one of the most esteemed garden centers in the greater Midwest.

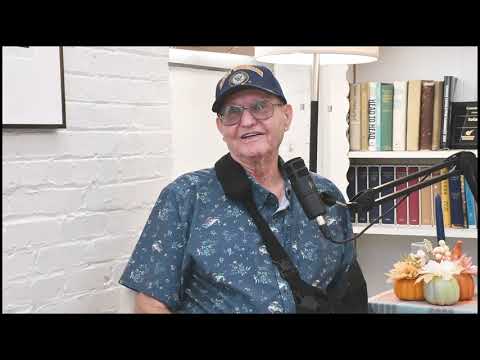

George returns a few minutes later and retakes his seat at the table. “She was looking for a tame gooseberry bush,” he explains. At 65, George Arnold is a tall man with close-cropped white hair. He’s the kind of man who, after sitting for long periods, begins to shift noticeably in his chair, as one who would rather be out working.

“I farmed all that time, even after we started the greenhouse,” says George. “But it got to the point where you’ve got to make a decision. You farm or you do the greenhouse, because you just didn’t have enough time in the spring for both. So, we went with what we figured would make a living.”

THESE DAYS Arnold’s Greenhouse employees more than 30 area residents — most of them on a part-time or seasonal basis — and caters to a customer base that arrives from all parts of the country to shop the 120’ x 288’ glass palace in search of the perfect plant.

“If you count every cultivar, tree, shrub, perennial, annual, vegetable, herb, and aquatic,” says Rita, Arnold’s plays host to nearly 2,500 varieties of plants.

George is not an immodest man but he doesn’t mind telling you that Arnold’s Greenhouse has the widest selection of plants of any garden center in the state: “There are bigger places and places that carry more of a specific kind of plant. Whereas we do a lot of small numbers of a wide range. So, for the individual consumer, you would be hard-pressed to find anything with a greater variety. Especially perennials. I think we’re good on perennials, annuals, vegetables, and herbs. We’re not real strong on woody materials.”

Even after 40 years, every plant is still hand-picked by the Arnolds, who continue to attend the country’s major garden shows and premier trial gardens, and whose passion for plant life across these many decades has never waned.

BUT IT DOESN’T mean that there aren’t hard times. The Arnolds’ fate — like the fates of the generations of farmers from which both Rita and George sprang — is bound by the caprices of nature.

Rita recalled a night three years ago when a cold front swept through Le Roy. It was about 2 a.m., the wind was roaring in their ears, “the temperature plummeted and the snow was just a-blowing in your face.” George saw that a panel on the greenhouse was peeling loose, a breakage potentially fatal to the Arnolds’ stock. “Well, after George got down from nailing that panel back in place, standing out there in that ice storm, he joked: ‘I don’t want to hear anybody complaining about the price of plants this year.’”

“HUMANS are a part of nature from the get-go,” theorizes George, when asked where his own love and his customers’ love of gardening originates. “We’re simply hard-wired to be with plants and animals.”

“Life began in a garden,” says Rita. “It’s where we started.”

“People look at it a lot of times with the misconception that it’s a luxury,” continues George. “But it’s not. It’s a necessity.”

The Arnolds come to their love of gardening down different paths. Rita has a scholar’s knack for describing in encyclopedic detail each of the varieties of flower or fern. George is more drawn to the total ecology of a plant. “The tying in of the plant and insect and animal worlds. The intertwining,” says George. “Basically, the whole circle of life business.”

“Right now,” said Rita, “we’re real concerned about the monarch butterfly population, because it’s been decreasing.”

“You’ve seen how butterflies flap around, going up and down, this way and that,” says George, “to where it looks like they don’t know what they’re doing. Well, they do. They’re paying attention to scent and to food source. See, they live their lives on that microbial level. And when they migrate, say if they’re going back down south, they will emerge from the pupa as an adult, stretch their wings, and when they take off, they follow the angle of the sun. That’s how they navigate. And each generation will do it without fail.”