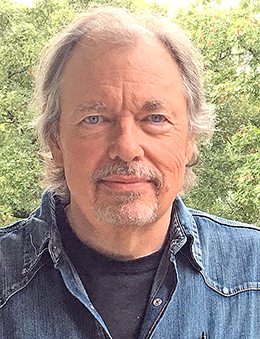

IOLA — Nathan Fawson is a man under fire.

And he wants you to know he is grateful.

Sitting in a consultation room painted a calming shade of neutral, Fawson — CEO of the Southeast Kansas Mental Health Center here — uses the word or a variation of it half a dozen times in explaining why his salary and benefits are more than $628,074. That figure has raised eyebrows and tempers in the community, a fiscal Rorschach test of one’s beliefs about the value of work, the cost of expertise, and who — if anyone — should pay for the public good.

“I’m very grateful that we’ve been able to offer fair, market-competitive wages to better support the community that coincidentally increased wages for management,” he says. “I’m grateful that we’ve been able to offer those competitive wages for expert services provided by management, allowing for those with that expertise to live and enjoy southeast Kansas rather than feel the need or desire to relocate.”

During the interview in the neutral room, decorated with a soothing triptych of what may be a beach scene, Fawson smiles often, gestures broadly, and sometimes refers to a printout summarizing the exponential growth of his six-county agency over the past decade. The center’s number of employees has nearly tripled since 2015, to 583; the budget has grown from $8 million to $75 million; and the number of patients served has expanded sixfold, to 25,906. The center has also, in recent years, offered medical and dental services, as part of its mission as a Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic and doubled its number of sites, to 30, including the clinic on Jefferson Street where our interview takes place.

But it’s not the additional employees or added services that has sparked a regional political backlash. It’s Fawson’s pay and benefits, which have more than quadrupled since 2020.

The SEKMHC serves six of the sickest and poorest counties in Kansas: Anderson, Allen, Bourbon, Linn, Neosho and Woodson. The median household income for Allen County is $57,618, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and about 10% of its residents lack health insurance. That compares with the Kansas median income of $70,333 and an uninsured rate of 8.4%.

In Iola, the seat of Allen County, a historic town of 5,400 on the Neosho River, the need for mental health services is one of those obvious things, like the need for rain to break a drought. Some townspeople told me that just about everyone knows somebody close who died by suicide or who were lost to drugs or alcohol. Local resident Sharla Miller, whose 19-year-old son Matt killed himself in 2019, started a conversation about mental health that included a local conference with representatives from the mental health center. The SEKMHC provides school therapists for districts in all six counties it serves.

Most of the center’s revenue comes from a variety of grants and Medicare and Medicaid. Its board of directors are appointed by the county commissions in the six counties. Each county appoints two representatives and also contributes a combined total of $550,120 in funding for this year, which amounts to less than 1% of the center’s budget. The county funds are earmarked for those not on Medicaid and who could not afford to pay for services — not salaries.

But this year, because of the heat over Fawson’s compensation package, the counties began decreasing their support. Three counties — Allen, Anderson and Neosho — dropped their support to just $1 — that’s right, a single dollar — for 2026, according to reporting by the Iola Register. Anderson County also stopped its quarterly payments for the last two quarters of this year. Linn County voted to contribute $0 for 2025 and 2026. Woodson County reduced its funding. Bourbon County has discussed the issue, but has not yet made a decision on funding.

Even if all six counties pulled funding, Fawson said, the center would continue to operate. Under federal law, nobody who needed emergency services would be turned away because of an inability to pay.

The controversy began in February of this year, when Allen County Commissioner David Lee called, according to Fawson. The commissioner had just seen the center’s latest available 990, from 2023. A 990 is the federal return tax-exempt 501(c)3 nonprofits are required to file annually with the IRS.

Lee asked him if the executive salary and benefits reported were accurate.

“I responded yes,” Fawson said. “Then he responded, ‘The community would disagree with those wages, and prepare yourself for a challenge.’ And that challenge has ensued.”

Fawson said he didn’t anticipate there would be a political concern about executive compensation until that call. He said he was surprised because he was confident in the wage analysis provided in 2021 and 2023 by the Hebets Co., a Phoenix-based consulting firm. The center retained Hebets, Fawson said, because its advisers are experts and would provide a reliable and objective analysis.

The center’s board of directors adopted the Hebets recommendation to increase salaries across the board. Fawson also said that because he was familiar with medical and behavioral health operations, the executive compensation packages suggested seemed appropriate to him.

Before the increases, Fawson said, wages at the center were below the 25th percentile nationally, and the goal was to bring them up to at least the 50th percentile. These increases were across the board, he said, and have improved the lives of the center employees and added to the southeast Kansas economy.