I knew what exile felt like, but nothing had prepared me to experience it again in my 70s.

I was 26 the first time I was forced to flee a dictator. It was in 1975, and I had to escape Nicaragua for resisting the regime of Anastasio Somoza Debayle, the last ruling member of a dynasty that had ruled the country for nearly half a century.

Back then, I was a committed revolutionary, ready to die for my country in the fight against autocracy.

The exile I find myself in now, forced to start life anew in Madrid, is one I never could have imagined — one imposed on me by the man who helped dethrone Mr. Somoza with the promise that Nicaragua would never again suffer under a dictator’s thumb.

In 2023, I, along with hundreds of other Nicaraguan intellectuals and dissidents, was stripped of my citizenship by President Daniel Ortega, who has now ruled Nicaragua for the last nearly two decades.

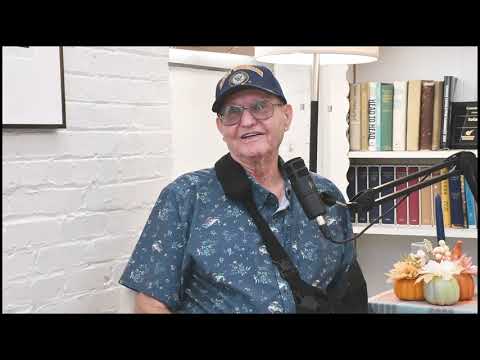

Even those of us who have sought shelter abroad no longer feel safe. Roberto Samcam Ruiz, a retired army major and vocal critic of Mr. Ortega, was gunned down inside his home in San José, Costa Rica, on June 19. No arrests have been made in connection with his killing, but he was at least the sixth Nicaraguan dissident to be shot, kidnapped or killed in Costa Rica since 2018.

It is the latest step in Mr. Ortega’s transformation from a onetime freedom fighter, my former comrade in the struggle against tyranny, into a full-blown dictator.

Autocrats have long wielded statelessness and control over movement as tools to punish political opponents. Now, it seems as if Nicaragua can be counted among the states that reach beyond their borders to silence voices perceived as threats by those in power.

It has been painful for me to watch my country backslide into violence and repression.

When I fled Nicaragua the first time, it was also to Costa Rica, to escape the Somozas’ iron fists. I was only able to return four years later, after the Sandinistas, the left-wing movement of which Mr. Ortega and I were both members, overthrew the dictatorship in 1979. It was a moment of hope, and I was ready to apply myself to the dream of a free and democratic country.

The guerrilla war that broke out with the contras, U.S.-backed right-wing militias looking to topple the Sandinistas, soon made clear that dream was a fantasy. The conflict, over which Mr. Ortega presided during his first administration, from 1985 to 1990, left Nicaraguans exhausted from death and scarcity — and from Mr. Ortega’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies, which I witnessed firsthand as an official in his government.

When Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, the opposition candidate, beat him in a landslide election in 1990, many throughout the country were relieved. Surprising many of her critics, she worked to ensure a peaceful transition of power and to mend a deeply polarized Nicaraguan society. But Mr. Ortega never got over his defeat, and his harassment of the new government drove many Sandinistas away from the movement, myself included.

Mr. Ortega returned to power in 2007, seemingly mellowed. But over time, he got to work dismantling the democracy we had so painstakingly built. He and his wife, Rosario Murillo, who became vice president in 2017, centralized power, scrapping presidential term limits and stacking the cabinet, the courts and the army with loyalists while keeping a facade of democracy. Favorable deals with Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela helped shore up a faltering economy.

The illusion of Nicaragua as a prospering, democratic state collapsed in the spring of 2018. When the regime tried to overhaul the social security system, peaceful protesters were shot. A spontaneous national uprising fueled by long-suppressed discontent followed. Thousands of Nicaraguans took to the streets, demanding the resignations of Mr. Ortega and Ms. Murillo. The couple responded with brute force. According to them, the protests constituted an attempted coup orchestrated by right-wing imperialists and treacherous opposition leaders.

Paramilitaries terrorized neighborhoods, shooting unarmed civilians and tearing down the barricades people had built to keep militias out. Doctors and other health care workers in public hospitals were fired for caring for wounded dissidents. The sight of hooded men riding in trucks and the bodies of protesters lying in the streets evoked chilling memories of the Somoza dictatorship. By July, the Nicaraguan flag had become a symbol of the resistance. Fear seeped into every home. Thousands, including Mr. Samcam, fled to Costa Rica, as generations of Nicaraguans had done before.

I remained in Nicaragua. Although I had broken with Sandinismo in 1993, I never thought Mr. Ortega would surpass Mr. Somoza in his tyranny.