I was 13 years old on Aug. 9, 1945, when the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan. We lived less than two miles from ground zero, but by some miracle, I survived. The glass door that collapsed on top of me didn’t shatter.

Other members of my family were not so fortunate. When my mother and I went to look for them, we found the bomb had taken the lives of five of our relatives: two of my aunts, my grandfather and my cousin all died from severe burns. My uncle, we discovered a bit later, died of radiation sickness after going to look for help.

By the end of 1945, the number of people who had been killed in Nagasaki was estimated at around 70,000. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima just days before killed 140,000. Altogether, an estimated 400,000 people were exposed to the two bombs. A large majority of them were civilians — mainly women, children and the elderly.

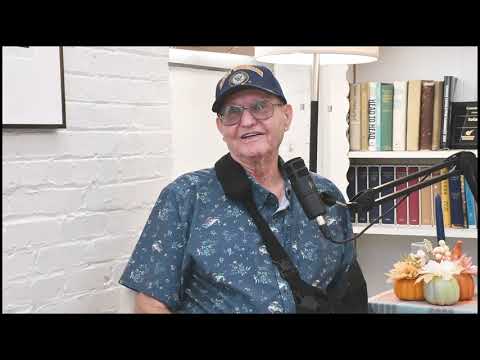

I recounted this experience in my speech at last December’s Nobel Peace Prize ceremony, when I accepted the award on behalf of Nihon Hidankyo, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations. The committee bestowed the prize on us in recognition of the work we have done over the past 70 years to build and strengthen the global taboo against the use of nuclear weapons.

We’ve done this by using the testimonies of hibakusha, as atomic bomb survivors like me and my fellow members of Nihon Hidankyo are known, to spread the knowledge around the world of what nuclear weapons actually do to human beings.

The explosion is seared in the memories of those who survived it.

Yoshie Oka, age 14, was on watch duty in a bunker in Hiroshima. “As I looked over to the other side of the room to speak to the person next to me, there was this flash of white,” she remembered. Ms. Oka was blown under some equipment but was able to get outside with a classmate who also survived. “The radioactive gas was like a fog, and we couldn’t even see 10 meters in front of us,” she said.

Another Hiroshima survivor, Setsuko Thurlow, has described what happened near ground zero, where thousands of students were helping clear fire lanes. “Nearly all of them were incinerated and were vaporized without a trace, and more died within days,” she said. “In this way, my age group in the city was almost wiped out.”

After a nuclear detonation, a large shock wave travels at hundreds of miles an hour. Beyond the immediate area, the blast causes lung injuries, ear damage and internal bleeding. The heat wave leads to severe burns and fires over a vast area, often leading to a giant firestorm. Nearly all of them were incinerated and were vaporized without a trace, and more died within days. In this way, my age group in the city was almost wiped out. Hiroshima survivor

Sumiteru Taniguchi, who was 16 and in Nagasaki, was riding his bicycle. “In the flash of the explosion I was blown off the bicycle from behind and slapped down against the ground,” he said. Mr. Taniguchi saw that the children who had been playing all around him were dead. He was more than a mile from the detonation but suffered severe burns to his back, left arm and left leg that quickly became infected. He spent nearly four years in a hospital recovering.

There is then the devastating impact of radiation poisoning. In Hiroshima, a boy, 7-year-old Toru Ikemoto, and his 9-year-old sister, Aiko, were indoors at the time of the blast, but within days they began losing their hair, developed fevers and could not eat, and their gums started bleeding. Though they both recovered from the acute stage of the condition, they succumbed from the delayed effects. Toru died when he was 11, and Aiko when she was 29.

Many children who were still in their mothers’ wombs at the time were stillborn or suffered birth defects. The fear of harming our own unborn children, combined with the stigma associated with being exposed to the bomb, has prevented many of us from ever starting families.

Today, the nuclear taboo is on the verge of collapse. The current wars in Europe and the Middle East involving nuclear-armed states, in which there are strong grounds for believing international law is being violated on a regular basis, and threats by the belligerents to use nuclear weapons are weakening the taboo over deploying them. India and Pakistan thankfully did not use their nuclear arsenals in a recent conflict, but the skirmish reminded us how wars between nuclear powers can happen.

Our Nobel Peace Prize sends a message to younger people that they need to be aware that we are facing an emergency — and the need to see a larger movement of young activists working to address the nuclear threat. Even here in Japan, not enough people see this as a pressing issue.

We have the solution in our hands: the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The treaty not only bans nuclear weapons and all activities related to their production, deployment and use, but also mandates that countries that joined the treaty provide support for people harmed by nuclear weapons in the past and for the cleanup of areas that were used for nuclear testing.